The civil engineer’s concerns about the end of mild weather turned out to be not only prudent, but prescient as well.

Our mild, wet January was pushed aside rather abruptly by a February that was more reminiscent of our “snowmageddon” of 2011 — when our own snow depth reached the top of the garage doors (!) at the Logger’s Retreat, and PG & E needed a week and a half to restore power to the area.

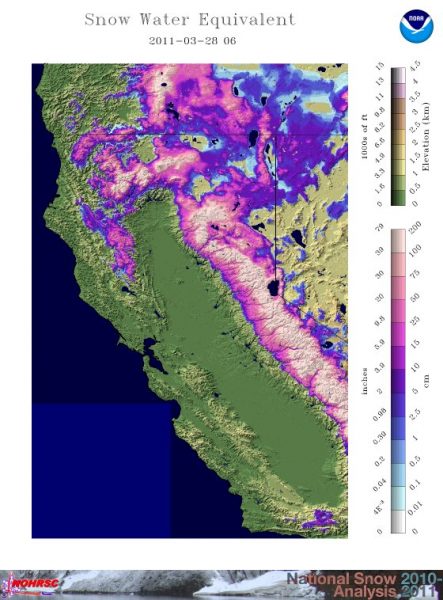

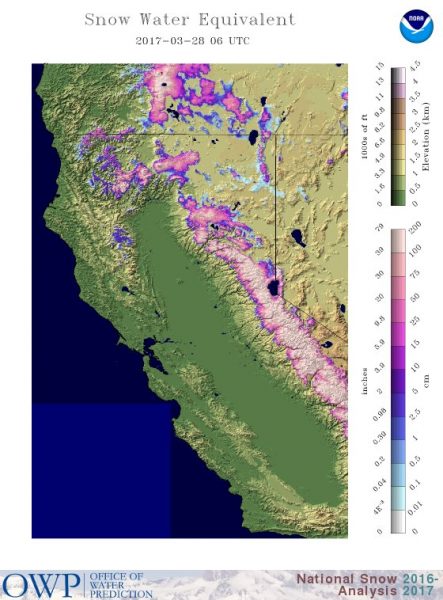

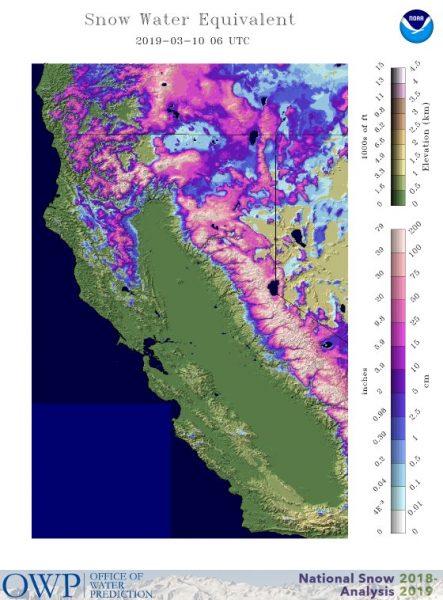

NOAA’s precipitation record confirms the similarity. (I’ve also included 2017 as a “dry” year for comparison. )

March 2011

March 2017

March 2019

February’s switch to more “normal” winter weather was the result of 2 major storms, both of which were “atmospheric river” events — which delivered a lot of moisture. The key difference from January storms was that these were accompanied by cold polar air, which finally brought the snow level down well below our 5000 ft elevation.

Despite that cold polar air, February’s snow depth at the Logger’s Retreat is still less than it was in 2011, but only because these storms were warmer; more of the precipitation fell either as rain or very wet snow that melted quickly.

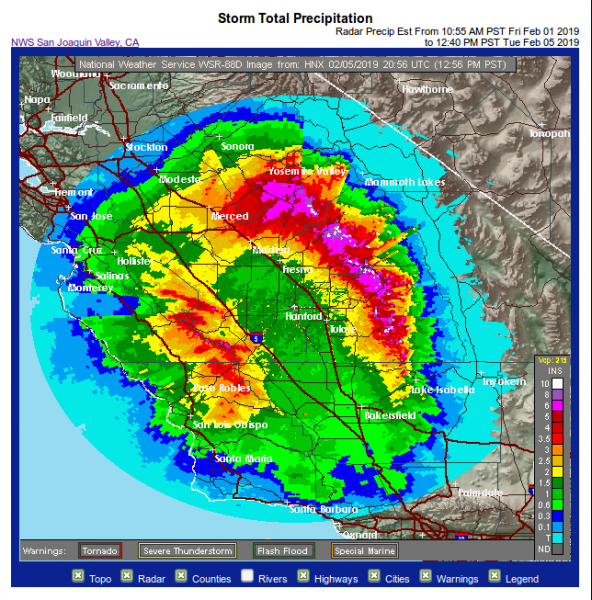

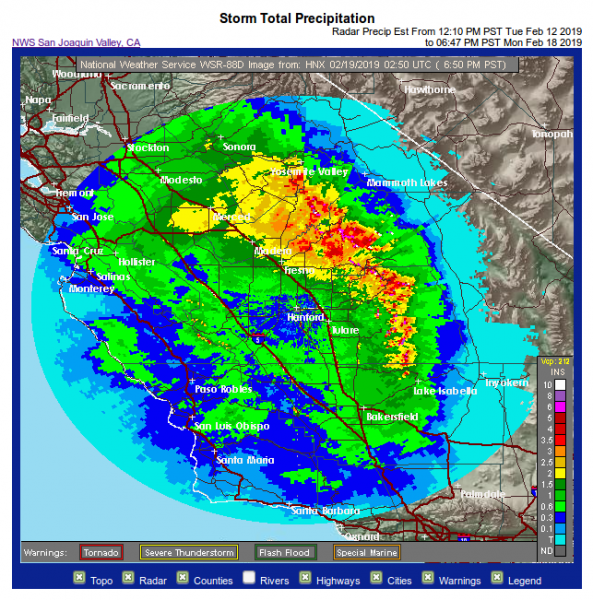

The first significant storm arrived in the first week of February — only a few days after we had finished our percolation tests. This is what the Hanford cumulative radar map showed at on the tail end of the storm.

After the storm I headed up to clear the driveway, and this is what it looked like when I arrived. Our driveway was completely blocked by a nearly-5 foot wall of snow!

I managed to find a small place to park alongside the road near the Narrow Gauge Inn’s driveway and then crossed the road on foot. After climbing over the snow wall, I strapped on my snowshoes and started on my way up to the Bobcat.

After walking about 20 feet, a key strap on one of the snowshoes broke. Grrr. I fumbled around in the deep snow and finally managed to make the snowshoe work despite the now-broken strap. I set out again.

After another 40 feet or so, a strap on the other snowshoe broke! Double-Grrr. This one was more difficult to work around. But the snow was definitely too deep to forego the snowshoes altogether, so I really had no choice but to make it work, somehow.

Note to self: rubber straps suck.

It took my fumbling around for another ten minutes or so for me to get that second snowshoe to stay on my foot — as long as I held my foot in just the “right” way. Which made climbing the hill, in deep snow, very slow and tedious.

Eventually I made it to the Bobcat, where I then had to use the snowshoes as shovels to free the blue plastic tarp covering it. The tarp was now mostly frozen in place by several feet of snow. Altogether it took me nearly two hours from arrival to actually start plowing.

I was reminded once again that before the fire, when I stored the Bobcat in the Logger’s Retreat garage, how little I had appreciated then the real value of that garage for times just like this. And it didn’t take much reflection to convince me that after plowing, the Bobcat would reside in the Trestlewood Chalet’s garage — at least for the next few weeks.

My task for the following day was to clear snow from walkways at the Yosemite Forest Lodge in Fish Camp. The hard part here is that you have to work the snowblower uphill, fighting gravity. Add to that a snow depth that exceeds the height of the snowblower, and you’ve got a tough job ahead.

But this time I was able to get the snowblower to ride up onto the top of the new snow and then guide it along the path. This allowed me to remove an upper layer of snow first, and get the snowblower all the way up to the Little Pine cabin fairly quickly. Then for the return trip down the path snow depth was no longer a problem and gravity was my friend.

I realized that this is the best technique to use whenever the snow depth exceeds the height of the snowblower.

Round Two

After about 10 days of rest, California got hit with the second storm. It was another “atmospheric river,” delivering roughly another 5 inches of rain equivalent precipitation to the Logger’s Retreat weather station. (Total recorded rain for the month was 10.73 inches.)

The complication with this storm was that the first few inches of precipitation came down as rain — saturating the foot or more of snow still on the ground. Then we got another few feet of cold, dry snow on top of that.

Again, the relatively warm temperatures were in many ways a blessing, in that if February had been just a few degrees colder, Fish Camp would have been digging out of more than 10 feet of snow!

By the time I was able to drive up to clear the second round of snow from the driveway, several groups of visitors had decided that our driveway would make a great snow play area. All that new snow had been trampled, packed down, and much of it polished smooth.

That might be great for sledding, but it’s not so great for a driveway.

Ah well; no harm no foul. The visitors wrapped up their snow play and moved on, while the Bobcat’s snowblower was able to chew up and spit out even the hardest snowpack they left behind. By sundown the driveway was clear again.

As with the first storm, my task on the second day was to clean up the walkways at the Yosemite Forest Lodge. This second time was tougher than the first, because the snow was deeper overall, and the rain-on-snow event had created a thick, heavy layer that was hard to get through, while the top foot or so was completely opposite: light, fluffy, beautiful.

Half way through the effort I got into a little argument with the snowblower and it responded by punching me a good one in the ribs. I must have either cracked or broken a rib because not only was it painful to finish the walkways, but the pain has only slowly diminished with time.

The moral to that story is: don’t pick a fight with your snowblower.

One of the casualties of this second storm was the front railing on the deck of the Little Pine cabin. The rain phase of the second storm saturated the snow on the Little Pine’s roof, and it slid off… all at once.

Normally the snow will just pile up on the deck in front of the railing. But it must have come down pretty fast this time because it went all the way to the railing, and then just kept going.

Now the remains of that railing are buried under about 5 feet of rock-hard snow. It will take a lot of melting before we’ll be able to even see it, much less repair it.